To access nature data, you first need to find it

Why locating nature datasets is slowing data teams down.

Welcome to the Nature Data Newsletter. Each month, we share insights with data enthusiasts, GIS experts, and investors learning about nature data.

We believe in a world where nature data is transparent, standardised, and easy to use.

As we build data infrastructure to make this future a reality, we are publishing what we learn along the way. So far, we have covered:

Scientific concepts - why we draw on scientific methods, tools, and theories to identify the core scientific concepts for interpreting nature; starting with plant biomass.

Domain specific criteria - how we organised a set of reproducible criteria into a structured methodology for selecting plant biomass data sources.

In this newsletter, we explore the first challenge faced by all nature data teams: locating nature data. The majority of the world's nature data is spread across hundreds of repositories, making it time-consuming to access relevant datasets for analysis.

In future newsletters, we'll delve into other nature data analysis workflow challenges - including integrating with data providers, data processing, data delivery, and more.

A practical example of locating nature data

Imagine you need plant biomass data to assess a forestry asset in Honduras. Your analysis requires data on plant aboveground biomass from the past five years, with at least annual temporal resolution.

A typical process to find datasets might look as follows:

Recognising that a search based on your specific criteria might not yield useful results, you instead enter a more generic term, plant biomass data, into Google. The search returns:

16 links to academic papers (8) and datasets (8) with spatial coverage outside of your region of interest (e.g. the Arctic) or experimental manipulations/context (e.g. soil nitrogen addition).

2 links to teaching resources on what plant biomass is.

2 links to data repositories.

0 links to plant biomass data providers.

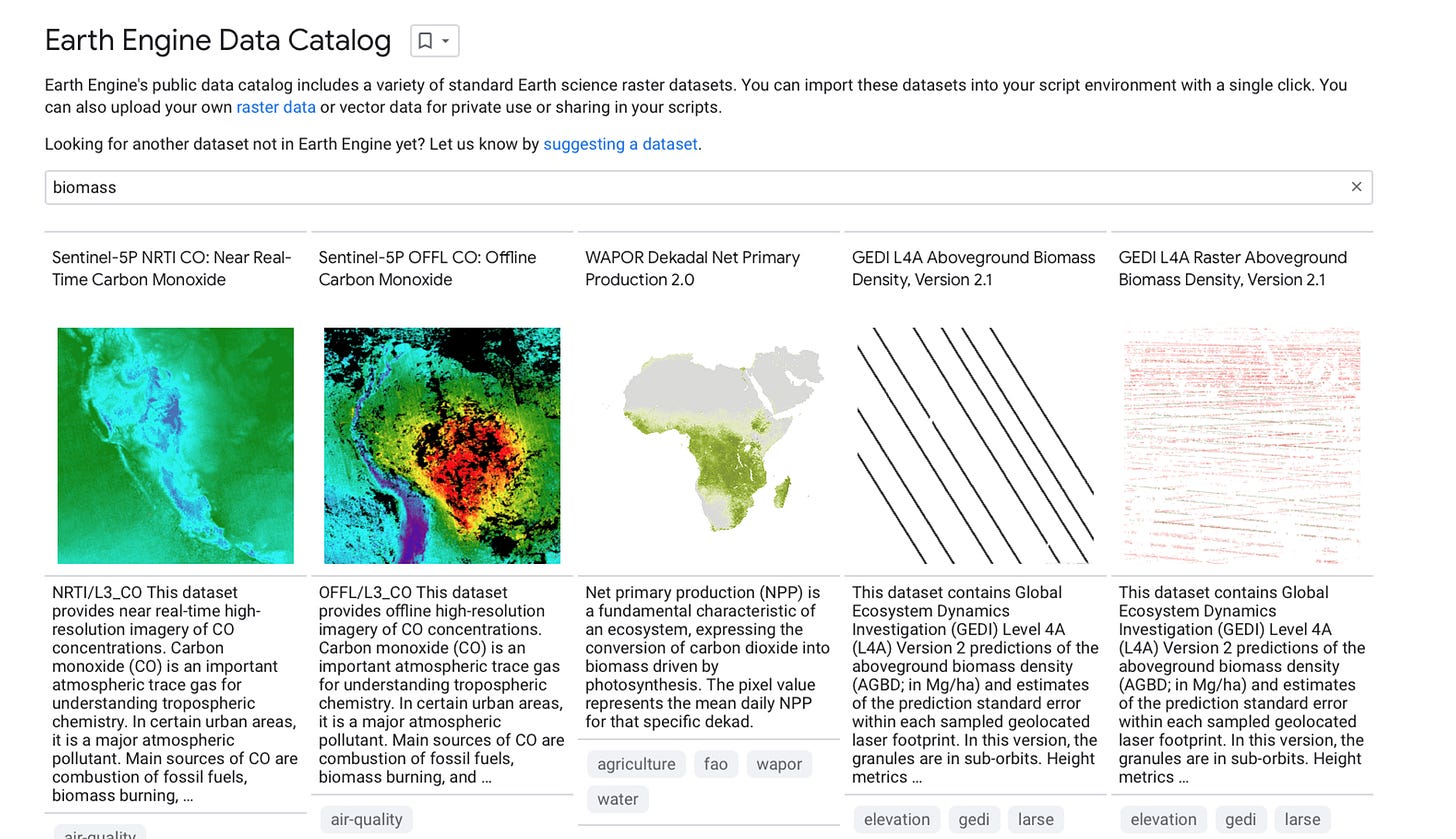

Next, you try searching Google Earth Engine’s data catalog:

Plant aboveground biomass, past five years, at least annual temporal resolution returns 0 results.

Plant biomass returns 0 results.

Biomass returns 10 datasets, but you need to dig into each one to verify it meets more specific criteria:

3 datasets are not plant biomass data.

3 datasets are raw GEDI instrument data.

The remaining 4 datasets are for single years, 1 of which has no spatial coverage in Central America.

Searching Microsoft’s Planetary Computer data catalog doesn’t provide the results you are looking for either:

Plant aboveground biomass, past five years, at least annual temporal resolution returns 0 results.

Plant biomass returns 0 results.

Biomass returns 4 datasets, but there is no functionality to filter by specific criteria or compare among them:

1 is raw Sentinel-3 satellite data.

The others are for a single year, 1 of which has no spatial coverage in Central America.

1 is from a commercial data provider with multiple year coverage, but it is a low spatial resolution product (roughly 4.6 km pixel size).

After searching 3 major sources of nature data, you have yet to find data that’s suitable for your analysis. Finding what you need may require digging further into academic research, government departments, or looking into commercial products.

Why is finding and accessing nature data so difficult?

Finding nature data to apply to analysis workflows can take months due to the following roadblocks:

Fragmented sources: Petabytes of nature data are scattered across hundreds of different repositories, archives, and organisations. Finding what you need takes time.

Missing selection criteria: Many open data repositories were designed for use cases beyond nature and are broad in scope (e.g. Google Earth Engine and Microsoft Planetary Computer). With no way to filter by relevant criteria, shortlisting potential datasets becomes a manual task.

Limited access: Acquiring datasets requires commercial agreements and technical integrations. This restricts data accessibility to teams with particular technical expertise, especially when dealing with multiple partners.

With no easy way to find, shortlist, and access nature data in one place, teams are forced to use workarounds. Spreadsheets listing known datasets alongside their criteria and limitations have become the industry standard.

We'd love to hear from others who are struggling to find and access nature data – drop us a line at hello@cecil.earth.

This newsletter is the first in a series that explores challenges in nature data workflows. We’ll soon discuss other issues that arise when integrating with data providers, processing data, delivering data, and beyond.

Coming soon: Datasets

After speaking with 50+ experts, data providers, and nature data community members about how they would like to find and access nature data, we decided to build Datasets.

Datasets is a public repository for easily accessing nature datasets.

This is the first component of Cecil's data infrastructure and is designed as the starting point for your nature data analysis workflow.

Here’s more on how we’re getting started:

Scientific concepts: Our initial focus for Datasets is the scientific concept of plant biomass. Over time, Datasets will expand to cover other scientific concepts.

Purpose-built criteria: Unlike broad scope data repositories, we are focused on improving how dataset information is organised using the criteria outlined in our last newsletter.

Transparent documentation: We have initially partnered with Chloris Geospatial, Kanop, Planet Labs, and terraPulse to list their datasets. We are working closely with these data providers to ensure Datasets includes transparent and standardised documentation.

Community contributions: Datasets will continue to be developed with the valuable feedback from our community. Please suggest any datasets you would like to see included here.

We’re currently testing Datasets with a small group of experts and will announce when it is live. Join the waitlist to be the first to access this public repository when we launch.

Notice Board

Chloris Geospatial share thoughts on how algorithmic forest carbon data can add value to Voluntary Carbon Markets.

Ecosia, the tree-planting search engine, has teamed up with Kanop to monitor its reforestation efforts from space.

Mozaic Earth have signed a strategic partnership with rePLANET to bring a low-cost biodiversity baselining solution to market in the UK.

Space4Good are offering a pilot program for our new deforestation alerts, prediction and reporting tools based on earth observation.

Meta, World Resources Institute and Land & Carbon Lab release groundbreaking 1m resolution global map of tree canopy height.

Planet release validation and intercomparison results for their Forest Carbon Diligence products.

International Food Policy Research Institute and Land & Carbon Lab update their spatial production allocation model on global crop production.

Do you have a nature data announcement to share with this community? Please contact hello@cecil.earth and we’ll include it in the next issue.

Thank you

A special thank you to everyone who supported Cecil this month with feedback, introductions, and advice:

Florian Reber, Romain Fau, David Marvin, Joe Sexton, Saurabh Channan, Simas Gradeckas, Oliver Dauert, Lauren Brown, Merry Schumann, Duncan Walker, Patrick Vandesteen, Franzi Schrodt, Maryn van der Laarse, Sean Chua, Laura Garcia Velez, Jinha Jung, Tommy Leep, Tom Quigley, Jeremy Yap, Steve Toben, Peggy Brannigan, Gregg Treinish, Tia Miller, Will Turner, Catherine Workman, Paul Hawken, Lowell Powell, Dean, Karl Burkhart, Kate Wing, Peter Tittman, Ben Halpern, and Beckett Sterner.

This newsletter is curated by Cecil. From curating data providers, to preparing data for analysis, Cecil’s nature data infrastructure helps teams access accurate and precise nature data. They are trusted by companies such as Foresight Sustainable Forestry, Kilter Rural, and Impact Ag Partners to manage data on 3,000+ natural assets and 3+ million hectares.

Enjoy the newsletter? Please forward to a friend.